The Battle of Midway Roundtable Opening Remarks

Welcome to the July issue of the Battle of Midway RoundTable. Before we begin I'd like to send a very special birthday wish to Col. John F. Miniclier, retired, who turned 101 on July 23rd. I still owe him a great deal of gratitude for writing an eyewitness account of his time with John Ford during the battle, when I was consulting on the 2019

Midway movie. He did get a credit in the movie. At some point I'll publish his account here on the RoundTable.

This month we have one very exellent article from Ron Russell. And yes it is the only one. However I'll always go for quality over quantity given a choice. The subject has been debated before, both here on the RoundTable as well as in other circles. While we will never have a definitive answer to the question it is nonetheless worthy of discussion. I have had my own fair share of discussions as well as some table top simulations playing out different scenarios. Some of these table top simulations included a number of experienced military personel. I've recounted these in past issues.

Also anyone that has any thoughts or comments on the 25 year anniversary of the Battle of Midway RoundTable please send them in to our email at

midwayroundtable@gmail.com. This does not have to be extensive. A few words of what the RoundTable has meant to you is just fine. Submissions will be included in the October issue and we look forward to hearing from you.

As a starter I'd like to give you a little bit on what it has meant to me. Having grown up in a household where my father served in the Navy in the Pacific I heard plenty of stories from him as well as a few that I managed to attend sitting on the floor a few feet away from him and his Navy buddy reliving the past. I also watched a TV show at my grandmothers house on the Battle of Midway and at that point, depite my very young age, found myself facinated by the battle then and ever since. Fast forward to the early 2000's while doing some research on the Battle found the RoundTable that I believe was still in the email form at that time. I remember getting emails and saving each one to my computer and re-reading it several times. Here was the actual men who were in the battle giving their own personal experiences. It just doesn't get any better than that.

So sit back and read the one and only article this month. I hope anyone that has any comments on it will sit down and write a few words. It's after all what we are all about.

WOULD HALSEY HAVE LAUNCHED THE TBDs?

____________________

13 June 2022

From: Tom Rychlik

Virginia

As part of my research on torpedo squadrons at Midway I decided to go back to the [Roundtable] archives….In issue 34 of 2008, Dusty Kleiss had a lengthy post on Halsey’s conclusions on using TBDs. I have read Dusty’s book and he recounts the surprise and concern for his classmate Tom Eversole [VT-6 pilot] on the morning of the battle. Dusty wasn’t aboard Enterprise in March when all the torpedoes missed or sank so he had to have heard that from others.

My question is, did the Roundtable ever uncover any more evidence that Halsey’s five conclusions, as set forth by Kleiss, would have become doctrine at Midway? All I currently have is Dusty’s comments. Dusty gives a reasonable explanation on why Halsey violated his own concerns over the use of the TBD/Mk13 weapons system to launch his attack on the afternoon of December 7 but goes on to say Halsey learned a lot about the TBDs during the Marshall Island and other raids and would not have used them as first strike aircraft.

If Halsey was so dead set against using the TBDs as first strike aircraft, did he recommend that Spruance and Fletcher not use them in the upcoming battle? Either he didn’t really subscribe to the policy Dusty says, or he didn’t want to dictate to Spruance and Fletcher what to do, or he simply forgot. Another option is that the fact that the TBDs didn’t get mauled at Coral Sea might have made him rethink this.

Last summer I read The Admirals on the four fleet admirals. The book talks a lot about Spruance but never mentions anything about Halsey developing a policy on the TBDs….This might generate some comments on the Roundtable.

With the highest regard,

Tom Rychlik

____________________

Tom’s questions relate to early Roundtable messages from VS-6 veteran Dusty Kleiss that suggested a BOM with Halsey as OTC (he was senior to Fletcher) would have been conducted much differently and a lot more effectively by leaving the TBDs behind and striking Kido Butai only with the SBD squadrons. Why that’s important lies in Dusty’s belief that Halsey held that view consistently until he was hospitalized and turned over his command to Spruance. That being the case, and with Halsey’s entire staff aboard the

Enterprise supporting Spruance, why were the Devastators launched on their futile mission in apparent opposition to TF-16’s—that is, Halsey’s—predetermined strategy?

|

|

|

|

Lieutenant Junior Grade Kleiss, May 1942

|

|

Dusty’s autobiography, 2017

|

To answer Tom’s questions, we begin by examining everything Dusty is known to have said on the subject, then search for historical evidence that either supports or refutes his thesis. We start with his two Roundtable message from 2008:

____________________

30 August 2008

Captain N. J. “Dusty” Kleiss, USN-Ret

Texas

BOM vet, SBD pilot, VS-6, USS Enterprise (CV-6)

How I wish RADM Lew Hopkins was still with us to discuss the "Group Grope." That is an event where an entire air group pounces on the enemy simultaneously. He stated: “I must say I never saw it executed as practiced."

In March 1941, VADM Halsey noted the success (or lack thereof) of our VT-6 squadron, launching their water-filled torpedoes at a stationary target. Only a few came near that target; most stopped, circled or sank. All torpedoes were dropped properly, at a speed lower than 100 knots, and altitude less than 100 feet.

In the late afternoon of 7 December 1941, VADM Halsey had nothing available on the Big E to attack the six Japanese carriers, except the VT-6 squadron and their questionable torpedoes. Half of our SBDs had been sent to Pearl Harbor, the other half were needed for scouting or anti-submarine patrols. Halsey decided to make a partial "Group Grope" attack just like his doctrine of March 1941.

Some of our SBDs, flying 800 pound smoke tanks, flew above our entire VT-6 planes (carrying live torpedoes) cruising at 96 knots. Several F4Fs flew above us. All of us above the TBDs had to make frantic "S" turns to avoid stalling. The F4Fs were shot down at Pearl Harbor, lacking fuel enough to reach the Big E. We SBDs were planning to land on the ocean because we couldn't navigate using "S" turns. A vertical burst of the Big E's searchlight 20 miles away led us home.

Halsey immediately ignored his doctrine of March 1941, prescribing a combined attack, since it was illogical with the three types of airplanes under his command: two were obsolete, had very short ranges, and had horrible weaponry [TBD and F4F]; the other one was modern, had twice their range, and had reliable weaponry [SBD]. Their speeds and stalls were so different that a massed group flying at the same speed (100 knots for our TBDs carrying a torpedo) was ludicrous.

Based on our Marshall Islands attack and other battles, Halsey came to the following conclusions:

1. Our SBDs, with their stepped down formation and frequent gunnery drills, had fairly good protection against enemy fighters.

2. Our F4Fs, with numerous gun failures, were desperately needed to protect our carriers. The SBDs did not need them.

3. TBDs might be used on short scouting missions. They would not be used in battle except against unprotected stationary targets.

4. Whenever enemy airplanes might threaten us, our planes should make a dogleg home, to avoid the enemy knowing the location of our carrier.

5. The most qualified pilot should lead formations; not necessarily the most senior one.

____________________

30 August 2008

Captain N. J. “Dusty” Kleiss, USN-Ret

Texas

BOM vet, SBD pilot, VS-6, USS Enterprise (CV-6)

What went wrong in the Battle of Midway? Answer: almost everything possible. We VS-6 pilots were instructed by Earl Gallaher [squadron commander] to keep our position plotted in a latitude-longitude diagram in the right hand corner of our plotting board. That way we could easily calculate the enemy position in a few seconds; much easier than a reference to Midway. We did plot Midway, since we were told to make a 40 mile dog-leg before heading home.

Just for a moment, suppose that the admiral in charge of our three carriers had told us of his intentions: was he going to follow the combined doctrine? Let us suppose he sent us instructions that each ship should proceed independently with its SBDs, as soon as he sent a signal, "proceed as scheduled." At dawn (0600), we would have been 200 miles north of Midway; we would have launched our F4Fs to protect the Big E and a few minutes later we would have launched our SBDs when the admiral gave us the "proceed" signal. Our TBDs would be in the hangar deck, and all of our SBDs would carry 1,000 pound bombs since we had a full takeoff run. Our information from Ady and Chase, from 0503 through 0552, was sufficient to locate the enemy.

If we had taken off at 0600, we could have flown at an efficient 160 knots, and we almost certainly could have found the enemy because we had practiced 20 mile wide searches without using radios. Certainly one pilot of six squadrons would have found the enemy carriers, and his squadron leader would have broadcast the enemy’s latitude and longitude. Six squadrons of dive bombers, from different directions, would have scored numerous hits at the enemy's MOST VULNERABLE time. That’s when most of his planes would be absent and the course of their carriers was predictable. Our 40 mile dog-leg home would not have given the enemy a clear picture of our location. Our YE-ZB system would have brought the pilots home because they'd have fuel enough to fly high and join bunches together for safety.

Of course none of this happened. RADM Fletcher kept silent about his intentions. All we knew was that we were about 90 miles east of Nimitz' planned position and that an enemy scout had just flown above us. Our flight decks were shuffled and reshuffled, putting TBDs on deck. At about 0700 we were launched, having been told "proceed southwesterly and attack enemy carriers as definitely located." We circled at 20,000 feet, expecting other SBDs to join us. Finally, at 0745 we were signaled, "proceed independently." We flew at 190 knots, using twice as much fuel as our normal 160 knots. By that time the enemy vulnerability period had vanished, and the projected location of the enemy had also vanished. We were truly in a "No Right to Win" situation.

The rest of that horrible BOM is well known. Many SBD planes had to land on the ocean. Many great TBD pilots were lost flying useless torpedoes….

____________________

Dusty repeats that theme nine years later in his book

Never Call Me a Hero (2017), p. 184-185: “After the Marshalls strikes, the pilots from Torpedo Six had cursed those torpedoes for failing them so spectacularly. Months earlier, I had even heard VADM Halsey barking to subordinates, telling them how he didn’t want any torpedo-laden TBDs to ever leave the hangar deck.”

Here we see an inconsistency in Dusty’s recollection. In his first 2008 message above, Halsey decides on his no-TBD strategy based “on our Marshall Islands attack and other battles.” That places his decision after the Marshalls-Wake-Marcus raids in February and March 1942. But in the quote from his book above, Halsey makes his decision “months earlier” than the Marshall Islands raid, which could only be in 1941, even before Pearl Harbor.

Why is that significant? It’s because the ambiguity of when the statement was made diminishes its importance. If it was to be an established CTF-16 policy, it would have been codified and recorded—it wasn’t. Instead, it smacks of the volatile admiral simply venting some emotional steam, as we know he would occasionally do. There’s a prefect example of it in

No Right to Win, page 237—Halsey, while visiting the codebreakers at Melbourne, learned that they were working to decipher Yamamoto’s flight plan during an upcoming tour of IJN bases, leading to an AAF mission to shoot him down. Halsey’s reaction: “GODDAMIT, YOU PEOPLE KNOCK OFF THIS YAMAMOTO BUSINESS. I’M GONNA GET THAT SONOFABITCH MYSELF!”

Now, did that mean Halsey literally intended to send a carrier task group deep into enemy waters, Doolittle style, so that his F4Fs might get a shot at the enemy admiral’s aircraft? Or was it simply an emotional outburst driven by how he’d

like see it happen, even though he had to know that there were good reasons for another strategy to prevail?

If Halsey told his subordinates that “he didn’t want any torpedo-laden TBDs to ever leave the hangar deck,” that begs the question, what are torpedo bombers doing on the hangar deck in the first place? Clearly, hauling aircraft to sea on the hangar deck with the intent to keep them there makes zero sense. Again, it sounds more like Halsey’s off-the-cuff emotions, not Halsey’s policies.

Dusty’s scenario of six TF-16 and -17 SBD squadrons striking

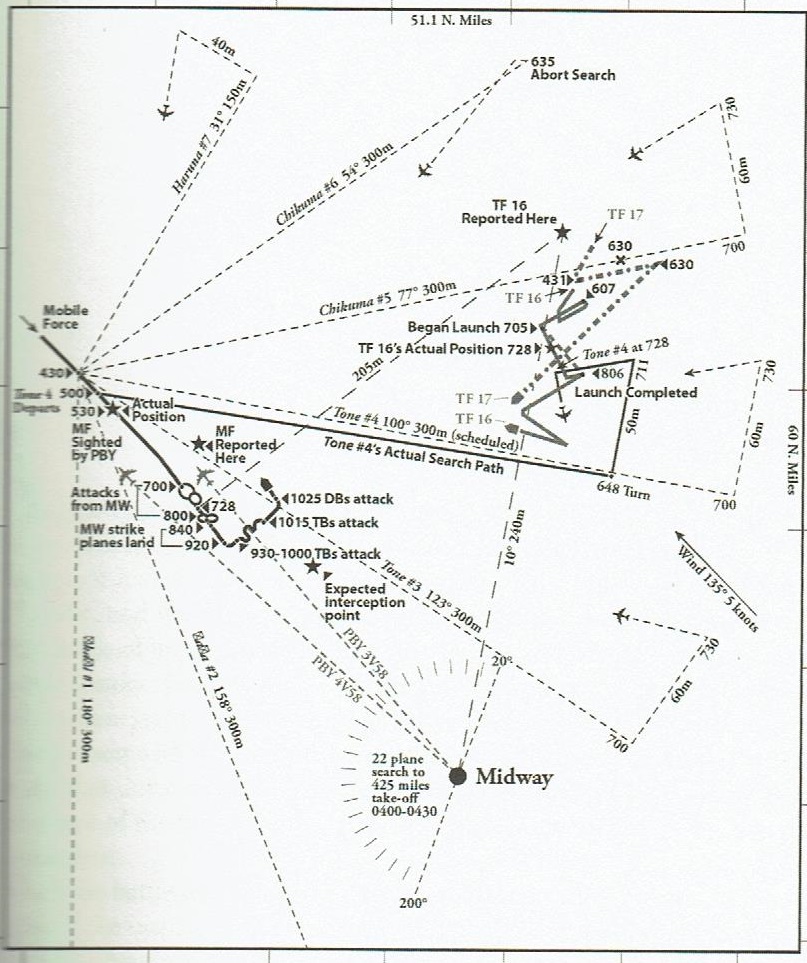

Kido Butai simultaneously because they launched closer to their target and weren’t delayed by TBDs has a solid ring to it if you ignore what the enemy might have done in that event. For one thing, take a look at the track of the Japanese scouts in Dallas Isom’s

Midway Inquest (2007):

Notice the two Japanese scout planes,

Chikuma #5 and

Tone #4. If TF-16 and -17 had been 90 miles closer to the Japanese fleet upon launch, would one of the scouts have found the American carriers much sooner than actually happened? Would it have spotted all three U.S. carriers instead of just one? Would its pilot have even seen the American strike force inbound on a reciprocal course? Would his warning have allowed Nagumo to launch his reserve attack planes while they were still preloaded with anti-ship ordnance? And would the lack of a low-altitude threat (TBDs) have left the Japanese CAP well positioned at high altitude as the SBDs approached?

Then, there’s that basic problem with going back and changing history: you can’t guarantee that doing so will result in better history. Any changes that you make inevitably lead to other changes that you didn’t foresee, and it’s doubtful that all of them would help your cause. The Law of Unintended Consequences always seems to interfere.

Debating BOM history and tactics with someone having the stature of Dusty Kleiss is not a comfortable exercise and is admittedly somewhat unfair—he’s no longer with us to offer continuing comment. But it’s unlikely that he’d be persuaded to alter his strongly-held opinion on the matter, which he articulated with conviction in his book and Roundtable messages. Further, there’s the problem that he’s the veteran who was there; I was not—all I have to go on is what I’ve read and what I’ve heard from other such veterans. That said, none of what I’ve read or heard from other such veterans supports any notion that Halsey’s “no TBD” pronouncements were ever more than momentary bluster.

Indeed, the evidence suggests that nothing of the sort was a factor in TF-16 planning. Spruance depended heavily on Halsey’s chief of staff, Captain Miles Browning, who at the time was an acknowledged expert in naval air operations. Browning, so far as is known, never recommended to Spruance that he should withhold the TBDs from the attack. In fact,

Never Call Me a Hero includes a quote from Dusty that Browning fully intended to use the TBDs from the outset: “…Captain Miles Browning…planned to launch all four squadrons, one after the other…Scouting Six and Bombing Six would go first…After that, Torpedo Six and Fighting Six would take off..." (pp. 188-189). Here, Dusty is acknowledging that the decision was Browning’s, not Spruance’s, suggesting that it would have been no different regardless which admiral was present on the flag bridge.

Moreover, Browning’s counterpart on the

Yorktown, Commander Murr Arnold, an even more experienced air combat veteran, similarly had no reservations about launching the TBDs. Again, the on-scene officer with the authority and best qualifications to decide attack strategy opted for the combined VSB-VT-VF doctrine considered essential in the BOM era as well as the entire war.

|

|

|

|

Yorktown air officer Murr Arnold

|

|

TF-16 chief of staff Miles Browning

|

None of this is intended to suggest that Dusty never really heard what he says he heard from Halsey, directly or indirectly, regarding withholding the TBDs. It only means that the commanders at Midway apparently decided that whatever faults the TBDs possessed were less important than the role they would play in the overall strategy. It would not have been a particularly difficult decision prior to the battle, especially for Fletcher, given the relative success of the TBD at Coral Sea. Nevertheless, does any of this mean that Halsey would have withheld the TBDs? Without the concurrence of Browning, which Dusty’s book seems to confirm would not have been forthcoming, it seems quite unlikely.

In summary, to answer Tom Rychlik’s questions:

1. Did the Roundtable ever uncover any more evidence that Halsey’s five conclusions, as set forth by Dusty Kleiss, would have become doctrine at Midway? No, quite the opposite.

2. Did Halsey recommend to Fletcher and Spruance that the TBDs not be used in the upcoming battle? So far as I’m aware, nothing that definite can be found in the recorded histories of the three admirals.

In the end, we’re left with a strongly-held opinion of one of the BOM’s most respected and celebrated veterans, but an opinion that’s open to question in the face of historical evidence suggesting otherwise. Still, the Roundtable has numerous members who are probably more qualified than me to tackle this subject, so by all means, send in your comments and we’ll have them in next month’s newsletter.

—RR